Small development teams with a laser focus on the fundamental purpose for an application achieve far superior results than larger teams. The development of instant messaging (IM) apps in China 15 years ago provides the perfect example of this. As someone who was in China there at the time before emigrating to the United States, I took notice of how a small team managed to succeed where bigger teams failed.

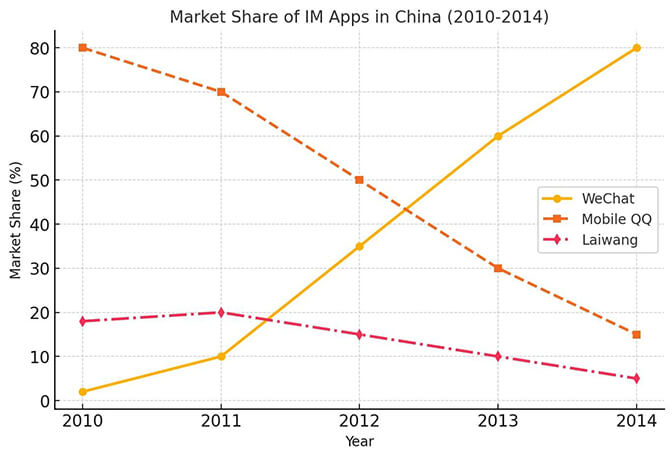

Back in 2010, there were three major development teams working on instant messaging apps. Among those three teams, WeChat was the smallest and had the least funding. In fact, the other two teams had financial and human resources that were at least a hundred times greater than Allen Zhang’s WeChat team.

Tencent’s own Mobile QQ team had abundant funding, a large workforce, and a well-established base of more than 400 million QQ users. The other team, Alibaba’s “Laiwang” team, had a user base of more than 200 million and received massive financial and manpower investments. To boost its app’s adoption, Alibaba’s founder Jack Ma even required company employees to recruit users. On top of that, Alibaba even offered users the incentive of covering all mobile data costs incurred by the Laiwang app, so they could enjoy the service without worrying about data expenses.

By contrast, Zhang’s WeChat team had only about a dozen people and little in the way of financial resources. In fact funding was so limited that they couldn’t even afford the mobile data expenses incurred from internal testing. WeChat also had no existing user base unlike its rivals.

Now at that time the work on instant messaging was taking place, 4G networks had not yet been deployed in China, and 3G coverage was still limited. The majority of mobile data traffic relied on General Packet Radio Service (GPRS) and EDGE cloud networks, both of which had strict Quality of Service (Qos) limitations. This meant that the number of times a file or data could be transmitted per minute was restricted as opposed to today’s 4G and 5G networks, which have virtually no such constraints on file size or transmission frequency.

Ironically, it was those technical limitations that became WeChat’s golden opportunity. Initially, WeChat’s user interface and functionality were far inferior to Mobile QQ and Laiwang, and WeChat also lacked the resources to attract large numbers of users.

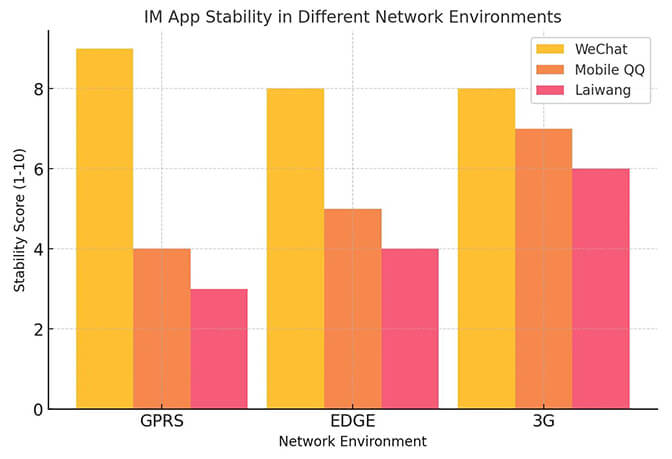

But unlike Tencent’s Mobile QQ and Alibaba’s Laiwang, WeChat was the only team that focused on extreme data compression for voice communication, optimizing their app to work within the strict bandwidth constraints of GPRS and EDGE networks.

WeChat adopted G.723.1 and CELP high-compression audio codecs, sacrificing some audio fidelity but reducing data usage to just 300–700 bytes per second. As a result, WeChat users could maintain stable connections even in subways, buses, and remote areas. On the other hand, Mobile QQ and Laiwang, despite their superior features and sleek designs, frequently disconnected due to their high data demands. Even though Tencent and Alibaba had massive user bases coupled with extensive resources for marketing as well as research and development, they ultimately lost to the underdog: WeChat.

WeChat adopted G.723.1 and CELP high-compression audio codecs, sacrificing some audio fidelity but reducing data usage to just 300–700 bytes per second. As a result, WeChat users could maintain stable connections even in subways, buses, and remote areas. On the other hand, Mobile QQ and Laiwang, despite their superior features and sleek designs, frequently disconnected due to their high data demands. Even though Tencent and Alibaba had massive user bases coupled with extensive resources for marketing as well as research and development, they ultimately lost to the underdog: WeChat.

Today, WeChat dominates instant messaging with more than one billon active users worldwide, and few people even remember the once-dominant Mobile QQ and Laiwang. In hindsight, if all three teams had started development three years later —- when 4G was already widespread — WeChat might never have had a chance to prevail and the victors could have been Mobile QQ or Laiwang.

The story of WeChat’s success at development is one I keep in mind. It shows a small team of developers can beat a larger one at innovation if a tight-knit group focuses on solving the user’s core pain points rather than simply relying on leveraging existing resources or expertise. It makes me think that a similar story may be playing out today in reports of the smaller team at DeepSeek advancing ahead of ChatGPT at developing artificial intelligence.

The takeaway lesson from the WeChat story is this: technological innovation comes about from figuring out what are the pain points that must be overcome to make the need for an application become a reality. It’s a lesson I’ve taken to heart and it’s foremost in our minds here at HYCO in the work we strive to do.